1. Introduction

In food and pharma industries hygiene is a must, non compliance can

lead to non quality, recalls or even legal pursuits. Hygienic design

must be seen comprehensively for the whole factory, including

building design, air handling, zoning, equipment design... One of

the basics is to ensure that the piping that will be conveying

the product is hygienically designed.

Hygienic piping design will indeed help in the following :

- Avoid materials accumulation that can spoil over time and

contaminate the finished product

- Optimize changeovers efficiency and duration

- Allow more efficient and shorter cleaning time, or even allow

the implementation of a CIP (Cleaning In Place) system

- Prevent foreign bodies generation from pipe parts

This page is focusing on good practices to apply when designing a

hygienic piping system.

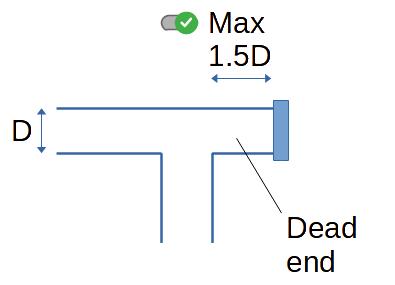

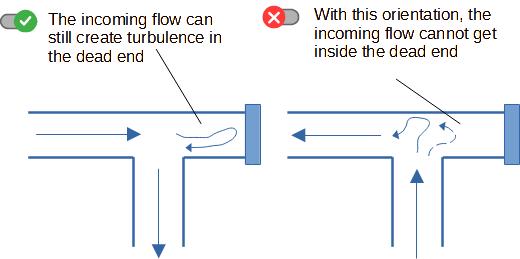

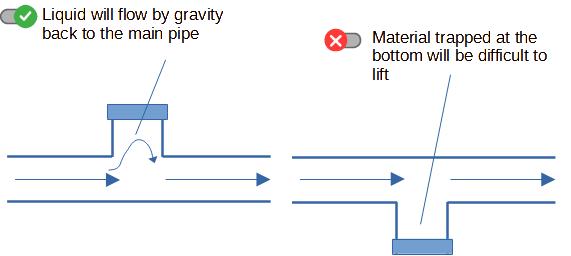

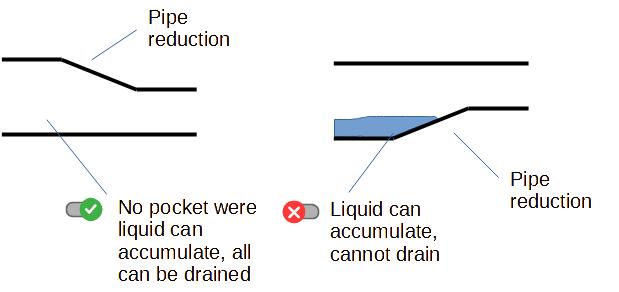

2. Avoiding dead ends

That is a fundamental of hygienic pipe design : avoid areas

where there will be no flow (those areas are also called "dead

ends").

If there is no flow, product will accumulate, deposit, have a long

residence time and will be prone to spoilage. It means also that

those parts of the pipes cannot be reached by cleaning agents for

example during CIP (Cleaning In Place), or can even be difficult to

access for operators manually cleaning the pipes in COP (Cleaning

Out of Place).

3. Pipe roughness and welding quality

Having a smooth surface will reduce the risk to harbor dirt and

bacteria in the asperities of the pipe. It is why a pipe with a

surface roughness < Ra = 0.8 microns will be recommended. The

material must be Stainless Steel to avoid risks of rusting ; the

correct grade of Stainless Steel must be chosen, especially if

the pipe will have to handle corrosive materials during cleaning

sequences for instance.

It is necessary to weld couplings to the pipe in order to be able

to assemble it. Welding needs to be controlled to make sure they

will not release foreign bodies, or harbor micro organisms due to a

rough surface. Welding must be :

- Done under inert gas coverage

- Smooth / polished

- Continuous (no gaps, no crevices)

The use of orbital cutting and welding is recommended over a fully

manual operation that will be less precise. It is recommended to

check individually all the pipes welding before

installation.

4. Pipe coupling

Designing and assembling properly pipe couplings is very important

to implement an hygienic pipe that will be easy to clean.

Coupling should be chosen and design to present the following

characteristics :

- Avoid gaps where product could accumulate

- Be designed to avoid overcompression of the gaskets, this could

damage the gasket, or push it on the inside of the pipe where it

could generate foreign bodies

- Ease the alignment of the 2 pipe ends when assembling, will

prevent gaps or on the contrary parts protruding on the inside of

the pipe

- Preferably be easily dismantable to allow inspection and

cleaning.

In practice, on the line, the operators must be careful to avoid

pipe misalignment (if the coupling are not designed to avoid it).

Especially having a gasket protruding on the inside of the pipe can

generate foreign body if the gasket starts to be damaged, foreign

bodies are a major cause of recall of products for pharma and food

industries.

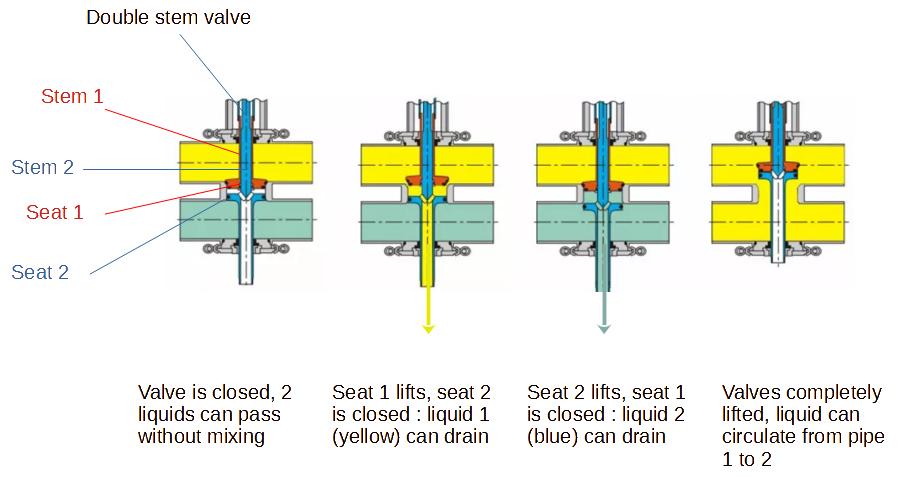

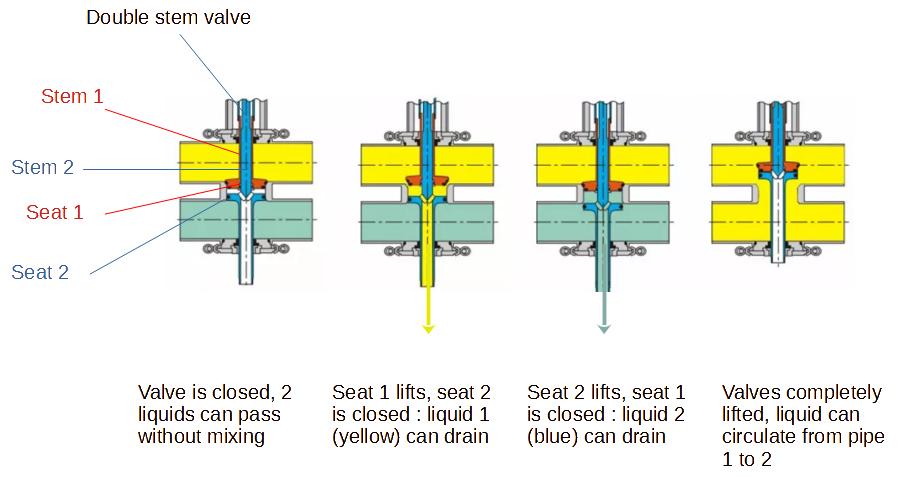

5. Valves

Simple valves design must be preferred when on the product flow in

hygienic piping, typically butterfly valves.

It is also possible to use a new type of valves, called mixproof

valves, which have also the advantage to be able to route safely

different products at the same time or solutions used for CIP ;

those valves are also designed to automatically clean the seats of

the valve during CIP cycle. Mixproof valves have a leak detection

feature, when one of the seats starts to leak, the product will be

drained, which will be visible.

6. Design Calculations for Hygienic Piping

6.1 Pressure Drop (ΔP)

The total pressure loss along a pipe run is the sum of frictional

loss and minor losses (valves, bends, reducers). Use the

Darcy‑Weisbach equation:

ΔP_friction = f·(L/D)·(ρ·V²/2)

- f – Darcy friction factor (Moody chart or

Colebrook‑White equation).

- L – Length of straight pipe (m).

- D – Nominal pipe diameter (m).

- ρ – Fluid density (kg·m⁻³).

- V – Mean velocity (m·s⁻¹).

6.2 Reynolds Number (Re) & Flow Regime

Re determines whether the flow is laminar (Re < 2000)

or turbulent (> 4000). For hygienic systems a turbulent regime

(Re ≈ 10 000–30 000) is preferred because it enhances mixing and

CIP effectiveness.

Re = (ρ·V·D)/μ

- μ – Dynamic viscosity (Pa·s).

6.3 Velocity Recommendation

Target a superficial velocity of 1–1.5 m s⁻¹.

This range balances shear stress (preventing product hold‑up) and

energy consumption.

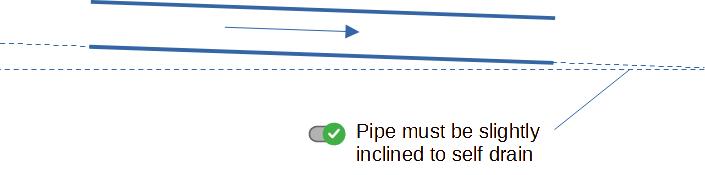

6.4 Minimum Self‑Drain Length

To guarantee complete drainage of dead‑end sections, keep the

length L_dead ≤ 1.5 × D (as already noted). For inclined

runs, a slope of 1–2 % ensures gravity‑assisted drainage.

7. Standards & Regulatory Guidance

Searches

for “hygienic piping standards” consistently surface the following

documents:

- 3‑A Sanitary Standards – Covers pipe

material, surface finish (Ra ≤ 0.8 µm), and joint design.

- ASME BPE (Bioprocessing Equipment) – Provides

detailed guidance on CIP/SIP, valve selection, and allowable L/D

ratios (typically ≤ 4:1).

- ISO 14644‑1 – Cleanroom classification,

influencing piping layout and accessibility.

- FDA 21 CFR 211 – Good Manufacturing Practice

(GMP) requirements for pharmaceutical equipment.

8. CFD & Simulation for Optimisation

If the hygiene of the piping is extremely critical, some

simulations can be done on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to

verify that:

- No stagnant zones exist (visualised with residence‑time

contours).

- Shear rates exceed the threshold needed for biofilm removal

during CIP (≥ 500 s⁻¹ for most dairy products).

- Pressure drop predictions match hand calculations within

± 10 %.

Typical workflow:

- Create a 3‑D CAD model of the pipe network (including

reducers, elbows, and valves).

- Apply a turbulence model (k‑ε or SST) and set wall roughness

to 0.8 µm.

- Run a steady‑state simulation for normal operation, then a

transient CIP simulation with hot water (80 °C) and caustic

solution.

9. Maintenance, Validation & Documentation

9.1 Routine Inspection Checklist

- Verify surface roughness (Ra ≤ 0.8 µm) using a profilometer.

- Inspect weld seams for porosity or cracks (radiographic or

ultrasonic testing).

- Confirm that all instrumentation ports are fully wetted during

CIP (use dye‑trace tests).

- Record torque values on couplings to avoid over‑compression of

gaskets.

9.2 Validation Protocols

For GMP environments, a Installation Qualification (IQ),

Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance

Qualification (PQ) are mandatory. Include the following

acceptance criteria:

- Maximum residual product after CIP < 0.1 mg L⁻¹.

- Pressure drop variation < 5 % between OQ runs.

- No detectable biofilm after 30 days of operation (ATP assay).

10. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What is the ideal pipe roughness for hygienic systems?

- Ra ≤ 0.8 µm (per 3‑A and ASME BPE). Anything higher increases

microbial adhesion.

- How long can a dead‑end segment be before it becomes a

contamination risk?

- Keep dead‑end length ≤ 1.5 × diameter. For larger diameters,

consider installing a dedicated purge line.

- Which valve type offers the best CIP performance?

- Mix‑proof (dual‑seated) or hygienic butterfly valves with

automated seat‑cleaning cycles are preferred.

- Do I need to calculate Reynolds number for every branch?

- Yes, especially for branches feeding low‑viscosity liquids;

turbulent flow (Re > 10 000) improves cleaning efficiency.

- Is orbital welding mandatory?

- While not legally required, orbital welding provides

repeatable, low‑roughness joints that meet GMP expectations.