Process control : control loop basics

Follow us on Twitter ![]()

Question, remark ? Contact us at contact@myengineeringtools.com

1. What is a control loop ?

2. How is built a control loop ?

3. PID Controllers in Control Loops

4. Step-by-Step Procedure to Tune a PID Loop

All industrial processes integrate a certain degree of automation, the basics of process automation are actually control loops, this page is giving basics infos on control loops for students or Engineers looking for a reminder.

1. What is a control loop ?

How works a control loop ?

A control loop allows to regulate one process parameter linked to typically one sensor. The process operator is defining a set point, and the control loop is acting on the process to make sure the sensor information stays at the right value.

The actions on the process are very often to adjust valves, that will as a consequence change the flow of material, or of heating fluid for instance.

A closed control loop will therefore work the following way :

1. Define a set point

2. Make a measurement

3. Assess the difference in between setpoint and actual measurement

4. Make an action to the process by transmitting an order (for

example change a valve setting)

Then action 2 is repeated and the loop starts.

2. How is built a control loop ?

What are the components of a control loop ?

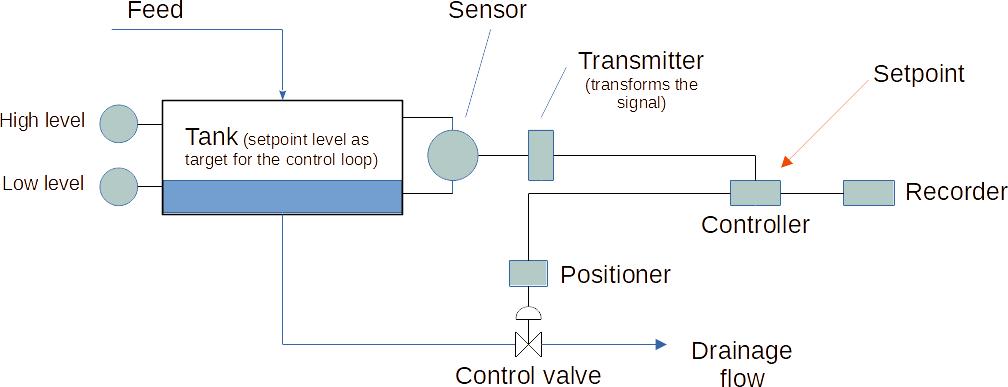

The following elements are making up a control loop (at minimum) :

- A sensor

- A transmitter

- A controller

- A positioner

- A control valve

Top 5 Most

Popular

1. Compressor

Power Calculation

2. Pump Power Calculation

3. Pipe Pressure

Drop Calculation

4. Fluid Velocity in pipes

5. Churchill Correlation

(friction factor)

Figure 1 : Example of control loop - tank level control

2.1 Sensor and transmitter

The sensor is making a measurement, typically measuring a level, a temperature, a pressure, a speed... and is linked to a transmitter. The transmitter is then sending a signal (for example what is the level in a tank) to a controller.

Signals can either be analogue (continuous transmission of information, with a digital current, or sometimes an air pressure)

2.2 Controller

The controller is the "brain" of the installation. It can be standalone but in most cases in modern installation, it is managed centrally by a large PLC that can be programmed.

2.3 Positioner and control valve

The positioner is ensuring that the valve is opened according to the setpoint given by the controller. It is on the actuator of the of the control valve, will measure the actual position of the valve, and if there is a need to modify the opening, will act on the compressed air of the actuator to adjust the opening.

2.4 Other components

It is possible to have other components such as a local indicator displaying the sensor output, or a recording system to be able to record a process value over time. There can be also some independent items such as low and high levels.

3. PID Controllers in Control Loops

What is a PID Controller?

A PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controller is a control loop feedback mechanism widely used in industrial control systems. It continuously calculates an error value as the difference between a desired set point and a measured process variable and applies a correction based on proportional, integral, and derivative terms.

PID controllers are crucial in control loops because they provide a robust and efficient method to automatically adjust process variables to maintain them at desired set points. They are used in various applications, from temperature and pressure control to flow and level regulation.

3.1 Understanding P, I, and D

- Proportional (P): The proportional term produces an output value that is proportional to the current error value. It responds to the present situation of the process.

- Integral (I): The integral term is proportional to both the magnitude and the duration of the error, it is the sum (integral) of past errors. It helps eliminate the residual steady-state error that occurs with a proportional-only controller.

- Derivative (D): The derivative term responds to the rate of change of the error. It predicts the future behavior of the error and helps to dampen the system response, reducing overshoot and oscillations. It is however sensitive to noise.

4. Step-by-Step Procedure to Tune a PID Loop

Tuning a PID loop involves adjusting the proportional, integral, and derivative gains to achieve the desired control performance. Here is a step-by-step guide:

Step 1 : Set Initial Values:

Start by setting the integral and derivative gains to zero.

Set the proportional gain to a low value.

Step 2 : Adjust Proportional Gain (P):

Gradually increase the proportional gain until the system starts to oscillate. (important note in critical processes (e.g., high-pressure boilers), open-loop bump tests or model-based methods are preferred for safety instead of forcing oscillations)

Note the gain value at which sustained oscillations occur. This is known as the ultimate gain (Ku).

Reduce the proportional gain to about half of the ultimate gain.

Step 3 : Adjust Integral Gain (I):

Gradually increase the integral gain to eliminate steady-state error. Increase "I" slowly and consider anti-windup limits.

Monitor the system response to ensure it remains stable.

Step 4 : Adjust Derivative Gain (D):

Introduce a small derivative gain to reduce overshoot and improve system stability.

Gradually increase the derivative gain while monitoring the system response.

Note : D is rarely used in slow processes (e.g., temperature) because measurement noise makes it counterproductive. When used, derivative should often be based on the process variable, not the error, to avoid reacting to setpoint changes.

Step 5 : Fine-Tune the Gains:

Make small adjustments to the proportional, integral, and derivative gains to optimize the system response.

Use simulation tools or real-time monitoring to evaluate the performance.

Step 6 : Test and Validate:

Test the tuned PID controller under various operating conditions to ensure robustness.

Validate the performance by comparing the actual response with the desired response.

FAQ: Process Control - Control Loop Basics

1. What is a control loop?

A control loop is a system that regulates a process parameter (e.g., temperature, pressure, level) by continuously measuring the parameter, comparing it to a set point, and adjusting the process to maintain the desired value.

2. What are the main components of a control loop?

The main components are: - Sensor: Measures the process variable. - Transmitter: Sends the sensor signal to the controller. - Controller: Processes the signal and determines the necessary action. - Positioner: Ensures the control valve is set to the correct position. - Control Valve: Adjusts the process based on the controller's signal.

3. What is a PID controller?

A PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controller is a feedback mechanism that calculates an error value (difference between set point and measured value) and applies corrections using proportional, integral, and derivative terms to maintain the desired set point.

4. What do P, I, and D terms in a PID controller do?

- **P (Proportional):** Responds to the current error. - **I (Integral):** Eliminates steady-state error by summing past errors. - **D (Derivative):** Damps oscillations by responding to the rate of change of the error.

5. How do you tune a PID loop?

Tuning involves adjusting P, I, and D gains: 1. Set initial values (I and D to zero, low P). 2. Increase P until oscillations occur, then reduce to half of the ultimate gain. 3. Increase I to eliminate steady-state error. 4. Add D to reduce overshoot. 5. Fine-tune gains and validate performance.

6. Why is the derivative term rarely used in slow processes?

In slow processes (e.g., temperature control), the derivative term is sensitive to noise, making it counterproductive. It is often omitted or based on the process variable, not the error.

7. What is the ultimate gain (Ku) in PID tuning?

The ultimate gain is the proportional gain value at which sustained oscillations occur. It is used as a reference to set the P gain (typically half of Ku).

8. How do you test a tuned PID controller?

Test the controller under various operating conditions to ensure robustness and compare the actual response with the desired response for validation.

9. What are common applications of PID controllers?

PID controllers are used in temperature, pressure, flow, and level control applications across industries such as manufacturing, chemical processing, and power generation.

10. Are there tools available for PID tuning?

Yes, simulation tools and real-time monitoring systems can assist in tuning PID controllers and evaluating their performance.